|

To celebrate our Aussie Desert Dogs fundraiser, we are thrilled to present the wonderful photographer behind the prints, Sam Gummer. We were interested to hear from Sam about her experiences living in Yuendumu, as well as her involvement with the Aussie Desert Dog Program. All of Sam’s stunning photos are available on our shop website. Each are printed on Museum Standard Pigment Ink on Archival Rag Paper, measuring 42 x 30cm. Please enjoy our interview with Sam.

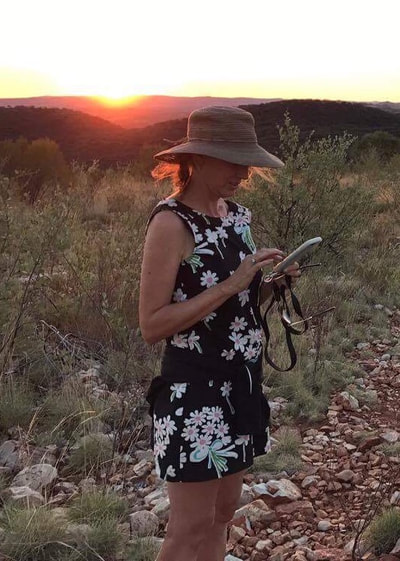

Dog Stories Sam, many of your photographs show dogs in them, and often their interactions with people....what is the role of dogs (in Yuendumu) for the Warlpiri people? Aboriginal people have always lived very closely with their dogs and a distinctive feature of most remote communities is the large number of dogs in communities. This is no different for the Warlpiri people of Yuendumu, where dogs can be found in homes, sunbathing on the roads, sitting with their people at the art centre, or waiting at the doors of the shops, clinic, dialysis unit and school classrooms! The dogs are given free range, choosing where they roam and with whom. Camp dogs hold a place of significance in Aboriginal culture and form an integral part of the Warlpiri society, featuring in traditional Dreamtime stories, song lines and artwork. Warlpiri people tell me that their dogs serve numerous purposes for them, including companionship and protection from physical and spiritual threats, warning them of impending danger and alerting them to intruders, human or otherwise. You've been working with Aussie Desert Dogs for a while now. What is your personal connection with dogs in Yuendumu, ADD and of course, Gloria Morales? I returned to Australia in 2015 for personal reasons, leaving my two beloved dogs Poppy and Jock with my ex-partner in the UK. I was filled with guilt and was not adjusting well to this extremely difficult but necessary decision. On talking to a friend in the UK about it, she reassured me I had done the right thing, saying ‘just make it count Sam, make it count’. When the opportunity arose to go out into the desert and photograph ‘The Dog Lady of Yuendumu’, I embraced the chance! I was supposed to stay for two weeks, however two weeks became two months and eventually two and a half years. Gloria Morales is an amazing woman. It was an honour to work out in Yuendumu with her and the dogs, watching how she dedicated herself to looking after not only the ones in her care, but also all the ones in the community. She never turned a dog away, even when her little two bedroom house was overflowing. Every dog has a name and when I arrived, she had a list on the fridge of all the dogs she was looking after. There were 76 names! The love in that little house is endless, as is the laundry, the cleaning and the picking up of dog poo! Gloria is the assistant manager of Warlukurlangu Artists, which is a mammoth task in itself. She is effectively doing two jobs which both need round the clock commitment. I can’t begin to tell you how much I learned from her during my time there, from administering medicines, holding my judgment in check, balancing priorities, and refraining from vomiting at the sight of a maggot infested wound! I also learned a lot about love, loss, death, and forgiveness and by the time I left I was able to look back with fondness at my time with Jock and poppy with less guilt and sense of failure. Whilst I was living in Yuendumu, I looked after MJ, a little senior dog with no eyes but a big heart. Her family felt she was no longer happy with them as she had stopped eating, so they wanted her to live somewhere quieter, with less people and dog traffic. MJ thrived with me and in turn, she helped me overcome Jock and Poppy. Luna Azul joined us along the way, and we became a little family of 3. Sadly, MJ passed just before I left the community. We estimate that she was about 16! Luna is here with me on the Mornington Peninsula, now enjoying the sea life instead of the red desert! I continue to keep in touch with Gloria and do the socials for Aussie Desert Dogs. I had the pleasure of returning there for a number of months at the beginning of this year (2021), which was a great change, having had some long lockdowns in Victoria. Can you tell us a little more about how ADD started and about some of its achievements? Due to the remote locations of many Aboriginal communities and difficult access to towns and vet services, the number of dogs in any one household can become large and unmanageable, with dogs forming packs and becoming territorial. General maintenance is difficult with such large numbers of dogs, leading to disease, illness, and fights, subsequently resulting in camp dogs holding a wider reputation of being malnourished, diseased, aggressive, and uncared for. This can lead to the assumption that camp dogs are unloved and uncared for, when in actual fact the challenges of overpopulation, high cost and short supply of food in the small community shops, great distance to vet services, and limited understanding of animal care, are the primary contributors to the plight of the camp dog. Fortunately, there are some amazing not for profit organisations and individuals who are supporting communities with desexing programs and educational programs, such as Gloria “The Dog Lady of Yuendumu’, AMRRIC and the Warlukurlangu Dogs Program. Gloria works very closely with AMRRIC and Stephen Cutter, a well experienced vet who has been visiting communities for over twenty years. When Gloria first arrived in Yuendumu 20 years ago the dog population was out of control and many dogs were sick and hungry. Eventually, unable to sit by and watch any more, Gloria started to care for some of the sick animals, as well as arranging for vets to come into the community to undertake desexing and anti-parasite programs. Because Gloria had already forged strong relationships with people in the community through her work at the art centre, they were open to her advice and guidance as to how best to keep their dogs and pets healthy and happy and begun to seek her help when their dogs were sick. Over time Gloria named her work ‘Aussie Desert Dogs’. Warlukurlangu Artists help fund the desexing program as well as making regular contributions to Aussie Desert Dogs, so between the two organisations, Yuendumu and surrounding areas now boast much lower dog populations, less unmanageable dog packs and happier, healthier dogs and people. 1000 dogs have been rehomed and literally countless little lives treated and saved. We are selling your photographs to raise funds for ADD which relies on fundraising campaigns such as this one to keep going. Can you tell us how these funds will help ADD? Literally every dollar counts. Because the money goes directly to source (Gloria), it is put to good use straight away. Basic provisions such as dog, cat and even cow/horse feed are daily expenses, as are medical supplies, cleaning products, towels, and blankets. Wheelchairs, plastic pools for relief from the summer heat, collars, dog beds, feeding trays, jumpers and heaters for the winter, and storage solutions are also required. On a larger scale, donations for building work, fixing the outside cat pen and extensions have been invaluable. Gloria goes into Alice Springs every fortnight for food, which is a 7 hour round trip, so fundraising and donations can even pay for petrol. Emergency vet visits, such as when Moana had to be rushed in for a still birth, are costly. And, of course, Gloria also helps to provide food and necessities out in the community as well. $5 will buy two large cans of food. $10 buys a chicken. $25 pays for a vaccination for a puppy and $50 buys a new heater. It’s all relative and it’s all important! And so gratefully received! What was the most challenging about taking photos of the dogs and their people was portraying the true story of animals that are loved and cherished, whilst at the same time not glossing over the fact that life is tough out there. This isn’t a place with green parks and dogs just back from the salon and the houses aren’t freshly painted with flowers on the porch. Desert life can be brutal for both humans and animals, with scorching heat, parched land, and a red dust coating on pretty much everything. Aboriginal life is tough, with Warlpiri people baring scars from past and present. Dogs and animals play a special part of this unique life, rich in heritage, raw, resilient, and strong. Women's Ceremony Sam, these extraordinary photographs give us an insight into Ceremony that non-Indigenous people don't usually have access to. You've captured an obvious bond between the women and girls, and a certain mood. Can you explain what is happening in this series of photographs? ‘Women’s Ceremony’ is a set of photographs that give a small glimpse into the world of the living culture of the Warlpiri ‘Women’s Business’, where sacred cultural heritage and tradition is passed down from one generation to the next. It was such an honour and surprise to be invited by the Warlpiri women to take this series of photographs. Women’s business is sacred, and ceremonies are usually very secret and not open to photography of any kind. On this occasion however, this ceremony was more of a dress rehearsal for the main event, and the women were keen to get photos of their daughters and granddaughters as they undertook a ‘practice run’ for their approaching passage of rite into womanhood. Having respectfully left my camera in the troopie, I jumped at the chance to get it out when the Warlpiri women called on me! In traditional Aboriginal societies, men and women have distinct yet equally important roles, undertaking different responsibilities, tasks and ceremonies that benefit the community as whole. Teachings and learnings happen in Men’s business and Women’s business, with ceremonies taking place in these sacred forums. Men are not allowed to know what happens in Women’s Business and women are not allowed to know what happens in Men’s Business. Kinship is at the heart of Indigenous society, the three levels of this being Moity, Totem and Skin Names. Many tribes, including that of the Warlpiri people, continue to structure their society through Skin Names, which indicates a person’s bloodline, how generations are linked and how they should interact with each other, who they can marry (or not!) their roles, and responsibilities to one another as well as their place of Country, dreaming stories (Jukurrpa), sites and ceremonies. Traditionally in Warlpiri culture, the skin names for women start with an ‘N’ and ‘J’ for the men. There are 8 names for each sex, with the skin of the mother or father systemically informing the skin of a newborn. Names include Napaljarri, Japaljarri, Nangla, Jangala and so forth. This complex system informs the heart of the Warlpiri society and people. What really stood out to me during the preparations for Ceremony on this day was the fun the children were having and the chatter and laughter of women and girls as they made artifacts and painted each other. This had a great influence on the photographs I chose for the ‘Women’s Ceremony’ set, as it was important for me to show what great joy was shared that day as customs were passed down, cultural traditions respected and the journey from youth to adulthood observed and celebrated. Sam, your photographs capture the role of sport in this Aboriginal community. I can't help but be struck with the energy captured in the series of children playing cricket, but obviously football is important to this community too... how do you manage to capture such exquisite moments in time as these? Sport is extremely important to people out in their communities. Children enjoy basketball, football and cricket and Yuendumu also has a much-appreciated swimming pool. Most families will have a football team they support, and communities have at least one or more football teams and compete in community ‘sports weekends. Sport is an excellent way to working with the kids, so there are a lot of family and youth initiatives involving team activities and games. I usually have some form of camera on me and tend to take photos at any given opportunity. The photographs of the children playing cricket were taken during an on-country learning weekend that Yuendumu school facilitates once a year. There are three locations where families camp out in this area, at it depends on the young person’s skin name as to which place a family group will go. Over the week, culture and story are shared, traditions are handed down the generations and visits are undertaken to places of ‘Jukurrpa’ (dreamtime). There is much time for games and fun too! The kids love cricket and, on this particular evening, set up a game just as the sun was going down. It was that beautiful time of golden hour, when a hush descends around you and voices seems to echo a bit more, shadows stretch long and there is a slow pause before nightfall. We were already dusty from our days trekking and then we had all had to push the school bus after it got bogged in the sand, so by the time we got back to camp we were all really grubby! I had only been in Yuendumu for a month, so everything was new to me. When I look back on these photos I can smell the fire and cooking in the air, hear the laughter of the kids and feel the grit of sand in my hair. I remember feeling more free and alive than I had in a very long time.

0 Comments

We are very excited about launching our new exhibition Yilpinji Love Magic and Ceremony, today.

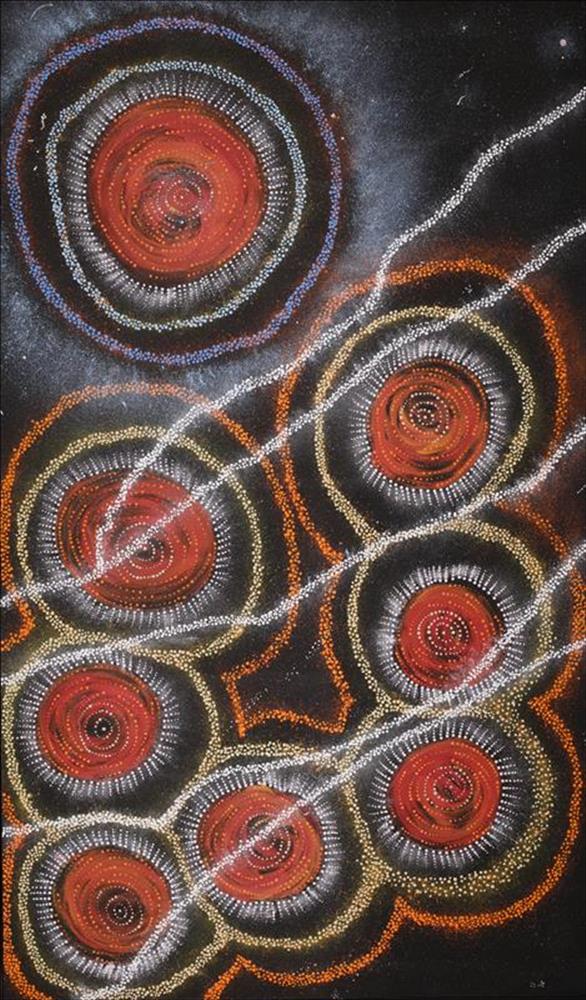

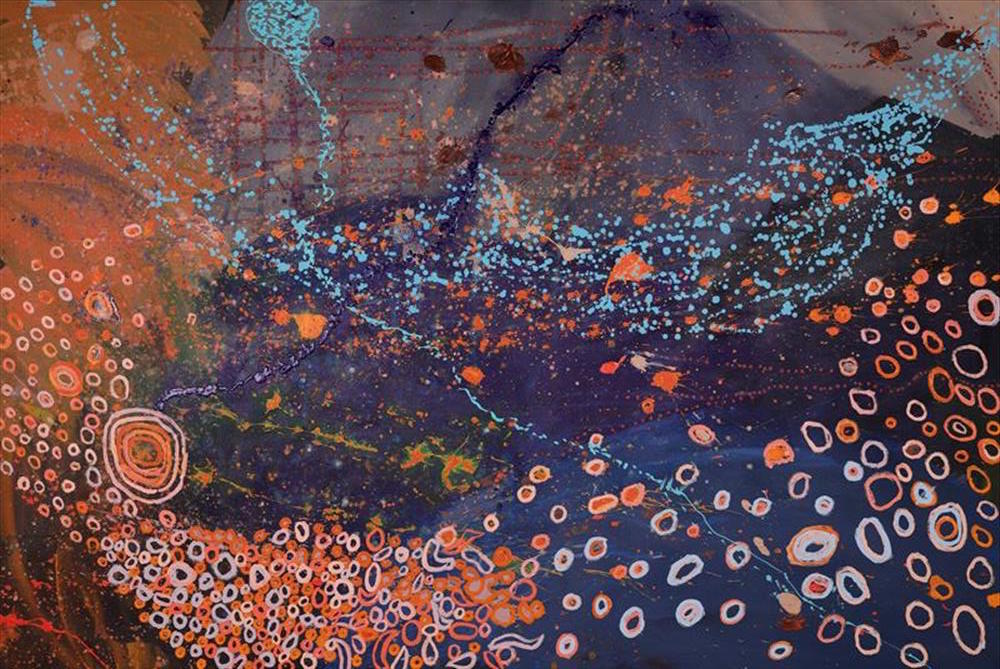

These limited edition prints by artists from Kukatja settlement of Wirramanu (Balgo Hills) in Western Australia as well as from Yuendumu and Lajamanu, which are Warlpiri settlements in the Northern Territory, have come about as the result of a cross cultural collaboration. The collaborators were Aboriginal artists, remote art centre staff and community organisations, a fine art printing house (Australian Art Print Network) and two highly respected non-Indigenous print-makers, Theo Tremblay and Basil Hall. Paintings of Yilpinji relate to moral and ethical behaviour and the transgressions that sometimes occur, and like other Dreaming stories they are attached to specific tracts of land. The narratives associated with the Yilpinji paintings provide guidance about how people should interrelate with one’s fellow humans as well as providing templates for interactions with other species and the natural world. These narratives have a range of iterations and like other Indigenous arts can be expressed trough a variety of forms. Narratives are deemed to be owned by certain individuals or groups, and a form of orally transmitted copyright underscored by communal ownership exists in kinship communities. Only parts of the stories are available to children or outsiders. They deal with important philosophical, spiritual, moral, ethical issues and subjects that concern all human beings. Yilpinji is poorly translated as ‘love magic.’ Some Yilpinji stories describe men behaving badly whilst others describe women behaving badly, in the sexual arena. Indigenous Australian use dance song and art to create a frisson with the audience, as in western story-telling, while facilitating teaching and learning about what constitutes proper behaviour in the sphere of sexual relationships. Works include depictions of objects that hold powerful love magic or relay information about gifted singers of love magic. Yilpinji can also be used a form of ‘sorcery’ and some works make reference to that malpractice. Other works relate to young and innocent love or are expressions of long-term faithfulness and the virtues of nurturing and respecting. The narrative includes reflection on worst possible case scenarios and consequences that arise from uncontrolled sexual passion. The paintings, prints and other artistic expressions of the stories can be understood as concentrated, abbreviated versions of these much longer and often secret narratives. All of the works in this exhibition relate in some way to the theme of love magic (Yilpinji). They also relate to many other subjects beyond Yilpinji, as part of long, complex Dreaming stories. They provide non-Indigenous people with a way of understanding a little understood part of this facet of Indigenous life. Abridged from original essay by Dr Christine Nicholls, Senior Lecturer, Australian Studies, School of Humanities, Flinders University, 2003. This essay was submitted to the Indigenous Studies Unit at Macquarie University in 2020 as an a component of the subject 'Indigenous Culture and Text'. The task was a comparative discussion between two texts chosen by the writer.

You might join me in paying my respects to the people and other beings everywhere who keep the law of the Land. (Yunkaporta, 2019) True learning is a joy because it is an act of creation. (Yunkaporta, 2019) Asking Echidnas for Help* - Understanding Power, Patriarchy and Pedagogy We stand at the crossroads to the most urgent decisions required in the history of humankind on the planet: if we move forward, as we have been doing, we go into the territory of ecological annihilation, mass species extinction and the breakdown of planetary survival systems. This comparative discussion will highlight the role of Indigenous epistemologies and pedagogies, discussed here as Knowledge Systems, through the examples of cultural burning by Djabugay author, Victor Steffensen, and, Indigenous memory technology, specifically sand talk symbols as mnemonic devices, as explored by Apalech author, Tyson Yunkaporta, in order to discuss Indigenous Knowledge Systems as a solutionary response to ecological destruction caused by western colonisation and ongoing colonialism in Australia. The concept of coloniality is used to refer to the connectedness between racism, capitalism and patriarchy generated through processes of globalised domination (Quijano cited in Tom et al, 2018 p.8) which describes attacks against Indigenous peoples and nature, including the commodification of life-forms and life-systems. I will explore the relational dynamics of Western patriarchal systems as discussed by both authors, and the impacts of these as institutional agents and agendas on Indigenous knowledge and ecological systems (Karanja, 2018). This will include the examination of the role of traditional Indigenous narrative, in solutionary, decolonising practices, and in navigating new relational systems for a new earth-referent paradigm (Tom, Sumida Huaman and McCarty 2019, Arabena 2015). As an initial observation it might appear that Yunkaporta’s book provides a pedagogical framework, or the ‘how’ to the ‘what’, or content of Steffenson’s knowledge systems; I intend that this discussion reveals that there are far more nuances and complexities to consider. Based on years of learning on Kuku-Thaypan country with his teachers, Awu-Laya men, George Musgrave and Tommy George, Djabugay man Victor Steffensen developed a system of cultural burning practice in response to ecological challenges faced on Kuku-Thaypan country. Steffensen, found this system was applicable to most ecological systems across Australia, and he presents a series of practice pedagogies or praction: these include spending time on country, learning to ‘read’ and develop sensitivity to country, relationship to non-human kin, responding to a variety of ecological systems, plants and soil types, and developing methodologies for the protection of water, riparian and other culturally and ecologically sensitive sites; and protecting living knowledge through intergenerational learning, participation and community well-being. This knowledge is published in his book, Fire Country - How Indigenous Fire Management Could Help Save Australia (2020). ‘Praction means applying the action for the wellbeing of the people, in a way that is culturally in tune with the natural world’ (Stefferson, p145). Based on his learning with Larrakia man, Old Man Juma, Apalech man, Tyson Yunkaporta applies symbolic icon, as a traditional Aboriginal sand-drawing device, in his book Sand Talk – How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World, to present a series of philosophical discussions to critique contemporary Western systems. His objective is to find the ‘how’ within the discussion of Indigenous Knowledge Systems and their applications, in order to identify solutions to global sustainability issues. From the supposition that the only way to store data long term is within relationships the author explores the notion of developing our minds in Indigenous ways in order to learn, to remember, to relate and to create a sustainable world. Thesis and Themes Indigenous Knowledge systems such Yunkaporta’s and Steffensen’s texts provide solutions to the degradation of ecological systems caused by Western land-use processes as part of Western patriarchal colonisation and ongoing colonialism. According to Arabena (2015), Indigenous processes and pedagogies, on the other hand, are earth-referent, inclusive, regenerative, underpinned by notions of respect, collaboration, reciprocity and humility; I will assert that both Yunkaporta’s and Steffensen’s texts provide examples of these pedagogies in the application of their Knowledge Systems. The essay aims to demonstrate the efficacy of the texts in offering potent solutions for the decolonisation of land, and the co-creation of self-organising systems, which are required to deal with current ecological dilemmas, including destruction of earth-systems such as water, soil and air, resulting in habitat destruction, species extinction and climate change. Both texts offer considerable material to the growing conversation of listening to Indigenous peoples and cultures for answers to the pandemic of human-induced ecological collapse across the planet (Tom et al 2019, Karanja 2018, Arabena 2015). This text comparison will explore the following interconnected themes and be structured in the following way: 1. Agents and systems of Western patriarchal land coloniality and direct impact on Indigenous Knowledge Systems and ecological systems 2. Indigenous knowledge systems and processes, (pedagogies) as mechanisms for land decolonisation and application to regenerative, synergetic, earth-protecting care-systems, (this is referred to as sustainable land-management practice in some professional sectors). The Emu Bossmen Colonising processes aim for domination of Indigenous peoples for access to land and in turn, domination over land, and, as Karanja states ‘colonial thought processes of Western science privilege and superiority over non-Europeans was the driving force for colonisation, and the dispossession of Indigenous people of their lands. Occupation was and is based on the scientific lie that the land was terra nullius, empty, and not owned by anyone (Karanja, 2018). Rose states that ’ethical dialogue requires that we acknowledge and understand our own particular and harshly situated presence’ (2004, p22), which is a vital component in truth-telling processes; through the texts I will assert a key similarity between Steffenson’s and Yunkaporta’s books, which supports the premise that institutional patriarchal systems and their inherent relational practices are the key barrier to effective ecological management in the modern Western world and in the current Australian context, and perpetuated by ‘unequal power relations, discursive authority, hegemony, and privilege play at the site of contact between Indigenous knowledge and Western science’ (Karanja, 2018). Throughout his text Steffenson describes numerous examples of his lived experience with such power dynamics, I referred to the boss men as the three P’s (of power): the police, the parks and wildlife, and the pastoralists... obstacles for cultural revival (2020, p25), including disrespectful and humiliating interactions with parks and wildlife staff, such as being given instructions without explanation, being present but not consulted at control burns as the token Aboriginal representative and not as an experienced fire-practioner, and being directed to ride in the tray of the utility with other Aboriginal men over rough tracks as the white ‘officials’ rode upfront. All these exemplify the relationally racist methods used to maintain the dominating power dynamic where, to not hear what is being said, not to experience the consequences of one’s actions, but rather to go on in one’s self-centric and insulated way is norm (Rose, p20). Yunkaporta focuses on another ‘P’ of institutional patriarchy, ‘Public Education’, characterised by relational dynamics including discipline, boredom, obedience, commitment to labor, compliance leading to national uniformity, social control, and ultimately fascism; including the manipulation of Indigenous peoples through rebranding, racial integration, reconciliation and homogenised identities (2019, pp 133-154). Yunkaporta asserts that schools are sites of political struggle because they are the ‘main vehicles for establishing the grand narratives needed to make progress possible’ (2019, p133). Steffensen describes his attempts to bring Indigenous Knowledge Systems into schools, realizing early on that ‘cracking the education nut’ was an almost impenetrable task (2020, p206). Western science acts as a ‘definitional and discursive hierarchical authority failing to acknowledge other Knowledges as complementary and equally valid (Dei, Hall, & Rosenthal, cited in Karanja 2018). Stefferson and Yunkaporta align in their views on relational difficulties inherent in Western scientific institutional practice where Steffensen describes knowledge as being forced into different categories and names, and lamenting how regularly Indigenous knowledge is appropriated when (science) ‘specialists come and go, creating their own projects and selling it as their own’.… in turn creating a ‘fragmented knowledge base’ (2020, p97-98). Although Steffenson concedes that science is a powerful tool, he acknowledges its relational and institutional limitations, suggesting an ideological power base that is ‘like a religion for some’… and that it’s’ common for people to think science is always done for good’…whereas, ‘there has certainly been some bad fire science…that is still influencing devastating environmental problems’ (2020, p101). Yunkaporta refers to western science an illusion of omniscience (2019, p47) because, unlike Indigenous understanding of biological networks, Western science systems do not ‘seek to find a way to belong personally to that system; they exist without feedback loops of knowledge, or lived cultural framework embedded in landscape and patterns of creation (2019, p196). These relational behaviours characteristic of Western patriarchal institutions, embody Yunkaporta’s story of the emu, the trouble-maker who ‘brings into being the most destructive idea in existence: ‘I am greater than you; you are less than me. Emu made hell of a mess running around showing off his speed and claiming his superiority, demanding to be boss’ (2019, p30). Yunkaporta warns about the need to contain narcissistic behaviours and communications because they threaten the basis of reciprocity which is needed for survival (2019, p31). Yunkaporta’s juvenile emu ‘bossmen’ closely align with Steffersen’s direct experiences with these ‘hardheads of society’ (2020, p205) and the ‘arbitrary controls and designs of (these) elevated individuals’ (Yunkaporta, 2019, p71). I would argue that identifying and describing these interactions is an act of resistance, and also necessary in the process of identifying decolonising methodologies for effective relating. Where the relating style is ‘narcissistic, disrespectful, non-listening’ (Rose p20), which both authors describe in their interactions with bossmen, police, pastoralists, scientific agencies, education and other officials, what constitutes movement forward from this point? If, as Rose asserts, this ‘nihilism stifles the knowledge of connection, disables dialogue, and maims possibilities whereby ‘self’ might be captured by the ‘other’’ (2004, p20), how do the authors describe effective development of relational processes? How can Self be captured by Other? Both texts offer numerous responses to this question, some of which are discussed below and include the role of narrative, yarning, subverting dualisms, truth-telling and utilising emotionally-engaging pedagogies inherent in knowledge systems. (This is only a brief summary as the scope of Yunkaporta’s and Steffensen’s offerings are too rich and broad to comprehensively cover here). Pedagogies of humility, joy and relation Karanja (2018) asserts the ‘primacy of land to Indigenous knowledge production and protection, and that Indigenous knowledge cannot be excised from its source, the land’. I would argue that they are interdependent and therefore that Indigenous Knowledge Systems are central to the protection of land. I will discuss some of the key components, as explored by Yunkaporta and Steffensen, that are both inherent in and act as protecting agent for this ‘sheer genius of symbiotic relationship’ (Yunkaporta, p2). Yunkaporta’s emu story is a powerful example of experiential narrative that constitutes an ‘epistemic, theoretical, pedagogical and empirical lens through which relationships with and between people and the natural world can be understood… (such) stories are theories that serve as the basis for how communities work’ (Archibald & Brayboy cited in Tom et al, 2019). The power of the emu story is that we can learn about this type of behaviour, through the powerful visual and behavioural icon of the juvenile emu as character, and work together to identify and understand (our own or others’) behaviours, and in so doing, strengthen relational processes. ‘The consequence of unmasking narcissistic singularity is that we embrace noisy and unruly processes capable of finding dialogue with other people and with the world itself’ (Rose p21). Yunkaporta and Steffensen highlight dynamic reciprocity, humility, patience, sharing and non-heirarchical approaches required in this dialogical process, focusing on First Nations’ equalising practice, yarning, which Yunkaporta describes as ‘structured, cultural activity that is a valid and rigorous methodology for knowledge production, inquiry and transmission’ (2019, p30). Rose argues that ‘colonising narratives are based in harmful dualities’ including nature/culture, male/female, civilisation/savagery, making relating impossible (2004, p19). Stefferson and Yunkaporta subvert the colonising dualisms or ‘othering’ associated with gender; Stefferson explains that women are also experienced fire practioners because they are the managers and therefore experts of their own food gathering lands (2020, p39), whilst Yunkaporta subverts myths about women as gatherers and men as hunters, challenges language that domesticates and feminises women’s tools (2019, p128), and points out that there is fluidity of gender in old age, where as elders engage with their own special business, at this time of life ‘men grow tits and women grow beards’ (2019, p206). Both authors offer numerous examples of utilising enriching pedagogy of the emotions, or learning through emotional engagement, and Yunkaporta asserts that ‘true learning is a joy because it is an act of creation’ (2019, p112). Steffensen and Yunkaporta align in their description of these pedagogical elements; working directly with self-organising systems on country where engagement with land is inherently haptic, kinaesthetic, social, highly-contextual providing opportunities to learn and value attitudinal and dynamic reciprocity, empathy, respect and humility. Steffensen describes the joy of learning when emphasis is placed on relationship building, and his own delight at observing that process, where the ‘activation of cultural understanding’ within non-Indigenous people brings them joy and hope; His face was lit up, he was free from a side of himself that was deprived of the truth and the freedom that comes from the land. I was happy for him and for the others…I could see the happiness in them too as they smiled in all four directions. It was a beautiful moment and everyone felt the love (2020, p94). Both authors emphasise the need for unity, and therefore working collaboratively with education agencies; more than ever we need a systemic response by education institutions to opportunities offered by Indigenous Knowledges, epistemologies and pedagogies. Theorists of critical pedagogies argue that Indigenous knowledges are vital for sustainability education, emphasising Indigenous ontologies as being essential to teaching and learning about land, in particular, the notion of humans as not separate to/from nature. Furthermore critical pedagogies actively criticise Western education as endorsement of colonial narratives including the domination and destruction approach to peoples and land (Greenwood, 2013). Yunkaporta argues that such a process would require the relinquishing of artificial power and control, (and an) immersion in the astounding patterns of creation that can only emerge through the free movement of all agents and elements within a system’ (2019, p94). This essay reiterates the value of truth-telling as key to decolonising practice which means exploring answers to questions that seek truth such as those asked through critical pedagogies: What happened here? What is happening here now, and in what direction is this place headed? What should happen here? (Greenwood, 2013). Throughout his book Steffenson makes clear the causative link between recent catastrophic fire events and historic mismanagement of lands in Australia: What a hell of a mess we need to start working through (2020, p85). There is no doubt that the devastation we see cast across the Australian landscape today has developed since colonisation (2020 p162). I would add this question and response from Yunkaporta to assist in truth-telling and critical pedagogy processes: ‘Why are we here? To look after things on the earth and in the sky and in the places in between’ (2019, p109). Conclusion A superficial comparison between the texts might suggest that Steffensen’s work focuses on the practical application of Indigenous Knowledge Systems to land, whereas Yunkaporta’s application of Knowledge Processes is designed to work upon our minds; or, that Stefferson’s relational priority focuses on healing land, where Yunkaporta’s relational priority is intra and interpersonal. Comprehensive consideration of the texts reveals the complexity of their discussions, with both authors synthesising abstract knowledge and practical application for human/planetary wellbeing. Each text highlights the importance of land to Indigenous people and the symbiotic interdependency of Indigenous Knowledge Systems and land; and each author has a comprehensive response towards the imperative to act, based on mounting evidence of impending planetary ecological collapse. My discussion has argued that both authors provide rich pedagogies of practice that are decolonising and healing for people and land. This essay has attempted to argue that right relationships, as presented by Steffensen and Yunkaporta, offer profound opportunities for social and ecological healing through the dismantling of dualisms, building relational capacity and supporting of self-organising systems. Both authors demonstrate that truth-telling and acknowledgment is of profound importance in healing processes for people and land by clearly describing and therefore subverting the relational systems operating in current western patriarchal power dynamics. Yunkaporta’s and Stefferson’s texts are necessary, inspiring and exciting tools in navigating a way forward within the Australian context. Future directions 1. A focus on research that gathers the stories of institutional ‘turnaround**’ or effective decolonising, through applied effective methodologies along with thorough and honest analyses of failed attempts would provide vital information for the protection of Indigenous Knowledge Systems and lands. An associated study on institutional emotional intelligence, (rather than individual emotional intelligence), would assist in identifying organisational systems and structures that reinforce mechanisms associated with coloniality, such as hierarchical structure, gender or culture dominated spaces, communication styles and decision-making processes. 2. Localised, regenerative movements, focusing on self-organising systems are gaining interest and application across the planet; Indigenous Knowledge Systems are key to the success of this movement. The process needs to be embedded in best practice, ensuring that Indigenous people define themselves and their Knowledge so that cultural appropriation and stereotyping is avoided (Karanja, 2018). 3. Western critical pedagogies have considerable progress to make before they can be regarded as being effectively synergetic with Indigenous pedagogies, and successfully integrated within the Australian school context; therefore an emphasis on teacher capacity-building and curriculum development in this area is urgently required. Notes *Yunkaporta describes the echidna as having the largest sized brain in relation to body size; he uses the echidna symbol in the discussing of complex problem-solving, and the need to listen to dissimilar minds and to take many points of view into account, to form networks of dynamic interaction and fertile ground; and to ask the following questions, ‘who are the real Indigenous People? Who among them carry the real Indigenous Knowledge and what aspects of Indigenous Knowledge are relevant in grappling with the creation of sustainable systems?’ **Yunkaporta’s definition of turnaround is synonymous with Creation, both during Dreamtime and now, an eternal cycle of renewal, continually unfolding. A smaller but similar turnaround happens at the neurological level when an individual learns something new (2019, p23) and extrapolating, when, at an organisational level there is cultural growth, or at a societal level, a critical mass of changed thinking that drives new behaviour. Cited References Arabena K, 2015, Becoming Indigenous to the Universe, Reflections on living systems, Indigeneity and citizenship, Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne. Greenwood D, 2013, A Critical Theory of Place-Conscious Education, International Handbook of research on Environmental Education, eds Stevenson R, Brody M, Dillon J and Wals A, Routledge, New York. Karanja, W 2018, An Inconvenient Truth; Centering Land as the Site for Indigenous Knowledge, Knowledge and Decolonial Politics - A Critical Reader, Anti-colonial educational perspectives for transformational change, pp 60-94, Vol 6, eds G Sefa Dei & M Jajj. Rose, DB 2004, Reports From A Wild Country – Ethics for Decolonisation, UNSW, Sydney. Steffensen S, 2020, Fire Country, How Indigenous fire management could help save Australia, Hardie Grant Travel, Melbourne. Tom MN, Sumida Huaman E, & McCarty TL 2019, Indigenous Knowledges as Vital Contributions to Sustainability, International review of Education 65, 1-18, 2019, https://doi-org.simsrad.net.ocs.mq.edu.au/10.1007/s11159-019-09770-9 Yunkaporta T, 2019, Sand Talk, How Indigenous Thinking can Save the World, Text Publishing, Melbourne. I get many amazing gifts doing the work i do and I am humbled by and grateful for them all... This exhibition gives me two of them....spending time with the art, reflecting, always seeing new things and especially in the quiet of the day. I also have the privilege to meet and work with people who are passionately engaged in their fields of endeavour. Please see Dr Ewen Jarvis' excellent summary of our first free community conversation, The Aboriginal Night Sky ... Kamilaroi woman and astrophysics student Krystal de Napoli spoke eloquently about the creative richness and layered depths of the songlines that often allow for the controlled and timely release of traditional wisdom. She also highlighted and explained how totally different sets of information can be gathered according to the gender of the researcher in the field especially in communities where there is traditional women's knowledge and traditional men's knowledge. Dr Duane Hamacher, Senior Research Fellow, Monash Indigenous Studies Centre, explained the importance of recognizing how rich indigenous systems of sky knowledge are and how reliant we are on outdated cultural knowledge often collected and recorded without appropriate methadological scrutiny. He stressed how much Western astronomy has to learn from traditional Indigenous Australian astronomy, revealed that in Australian Indigenous culture the stars often change names according to the time of year, and described the dark emu's movement across the sky noting its correlation to certain Indigenous initiation ceremonies. He also pointed out that Australian Indigenous people are often remarkable sensitivity to the subtle colouration of stars. Dr Jarita Holbrook, American astronomer and associate professor of physics at the University of the Western Cape, observed that many other indigenous cultures are aware of and have stories that refer to the hidden star in The Pleiades cluster, while noting that they acquired this knowledge without the use of telescopes. She also revealed that in some cultures these stars represent a group of males but in many more cases they represent women/sisters. In addition, she pointed out the challenges of being a female in heretofore male-dominated scientific disciplines, citing in one instance the natural propensity of young female students to giggle and young male students to strut: the result being that male students are often rewarded for their strutting, but the giggling of female students is rarely seen in a positive light. Jarita also drew our attention to the presence of mythologically resonant astral bodies like Algol, the Medusa star, which blinks a red eye at the earth every few days. Dr Ewen Jarvis, curator Yering Station Art Gallery, explained how the night sky resembles a library, i.e. a vast system of encoded narratives. He used examples from the 'Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters' exhibition at the Australian National Museum to draw attention to creative Indigenous engagement with earth and sky, and went on to question the degree to which Western empirical knowledge of the sky can benefit from the creatively rich and temporally expansive depth of Australian Indigenous sky knowledge. Each day I reflect on Hearth's journey with deep gratitude. Especially now as it's been a year since the business was launched and it's a time for reflection and celebration. I love each time a parcel arrives from Warlukurlangu and I get to unwrap the exquisite pieces. It's always such a thrill to see what the artists are doing next. I am grateful for the endlessly interesting and diverse interpretations that emerge from the artists at Warlukurlangu. I am grateful for the support Cecilia, Gloria and the team from Warlukurlangu give me. Their hard work, commitment, creativity and resourcefulness inspires me constantly. Hearth Galleries receives so much support and encouragement from the Healesville and Yarra Valley community and beyond. The stories and delight our visitors express is utterly heartwarming. There have been many tears of deep emotion; tears of connection, acknowledgment, realisation. Its a privilege to be able to represent wonderful Aboriginal artists local to the Yarra Valley such as Aunty Kim Wandin, Nikki Browne, Deb Prout, Gail Choolburra, Merilyn Merm Duff and Graham Patterson. Hearth is passionately growing our capacity in this area. I am grateful for my family and friends who have supported me every step of the way. It's been a busy exciting year and I wouldn't have achieved it without you. In this past year and from the first pop up at Healesville Senior Cits Club in April, renovated, opened and launched Hearth Galleries with a beautiful exhibition One Sky: Art from the Desert, we've had two exhibitions at Olivigna Winery, an exhibition of Leila Boakes' incredible acrylic works on canvas, Inner Life Outer World, a pop-up at the Unitarian Peace Memorial Church in Melbourne for NAIDOC Week, a celebration of all things Emu in the exhibition Jankirri is Emu, the Retrospective of the Old Mechanics Institute Gallery Healesville and then we finished the year with Sam Gummer's extraordinary photographs Stories of Yuendumu and a celebration of all things desert dog. Early in 2018 I worked at Worawa Aboriginal College in the Sandra Bardas Art Gallery and curated an exhibition for National Reconciliation Week at the CSIRO, working with the lovely Lisa Hodgson from Worawa. We've just launched a magnificent exhibition of significant large works from Warlukurlangu Artists at DoubleTree by Hilton in Flinders Street Melbourne. It was a delight to be invited by Jacinta Young who I worked with at Warlukurlangu last year and now is the Marketing Manager at DoubleTree. Grab the chance and check it out, the work looks magnificent in the space. Ten exhibitions for Hearth, (and my 11th in the year) that's almost one per month and the wealth of connections forged is well worth celebrating! We hope you will join us for a great opportunity in February... We are on the cusp of launching our Thank you by Hearth Galleries exhibition which will run throughout February. This is a chance for us to show our gratitude to all of you with some significant price reductions and a great opportunity to purchase a beautiful piece of art!! Come and see where the blue dots have landed... March is bringing an exceptionally exciting exhibition for Hearth Galleries, one that examines and challenges our perceptions of TIME...more brilliant works and dynamic discussion to come!! In gratitude, Chris x Hearth Galleries launches Warlukurlangu Artists at DoubleTree by Hilton, Flinders Street Melbourne

Thursday 17th January 2019. Exhibition runs til 17/3/19. I am very excitedly preparing for a new exhibition coming up in December...

Photographer and art therapist Sam Gummer will share her insight into life in Yuendumu through her exquisite photographs. These extraordinary images offer a window into the remote Aboriginal community of Yuendumu, depicting the diverse stories of the Warlpiri people, from traditional to contemporary, sombre to celebratory, creative to sacred, ancient to modern day. From ancient Dreamtime stories, skin names, sacred ceremonies, paintings and artefacts, to modern day clothes, music, art making and social media, the story of this community comes in the form of collective narratives woven over the tapestry of time. Gummer's work will be presented alongside the art from Warlukurlangu Artists in Yuendumu, where she lives and works. Gummer also works for Aussie Desert Dogs, an organisation funded by the art centre, that provides veterinary assistance, food, medical care and where needed, re-homing, for Yuendumu's dog population, and also a rescue response for injured and orphaned wildlife. Coats for Winter Campaign: to celebrate all things 'camp dog' throughout december, Hearth Galleries are generating a campaign to raise funds for the dogs who are homeless and cared for by aussie desert dogs, there are about 60 or so at present. They need coats in the cold winter months especially during the freezing nights. the small ones find it particularly tough-going in winter. If you'd like to make a dog jacket, donate one or buy one for the dogs of yuendumu, please visit Hearth Galleries or give me a call on 0423 902 934. Handpainted Dogs: a special part of this exhibition includes beautiful metal dogs, handpainted by the artists of Yuendumu. The metal dogs are made by inmates of the NT correctional facilities, then painted by Aboriginal artists in community. Each dog is vibrantly unique and based on the shape of a real dog that lives in Yuendumu, getting up to the usual fun and mischief around town! Limited number available. Contact us for more information or if you'd like to order one for Christmas. More dog stories coming soon...and stay tuned for a sneak preview of Sam's extraordinary work. Wednesday November 28th - Sunday 30th December Launch event 2pm Saturday 1st December Last weekend Hearth Galleries was launched with much excitement. Here are my thoughts on opening day...

'The hearth is a place to sit around a fire, a place of gathering, for stories and for celebrating shared culture. The hearth provides the flickering light of hope, collaboration and optimism. Within the word ‘hearth’ lies other words, heart, earth and art. My hope is for a celebration of art that expresses love for the earth, whether we are artists, curators, art-lovers, collaborators. This project would not have been possible without many of you here today. This project has been a collaboration from the start. In the 80’s Mum ran a successful gallery just around the corner, literally four doors away, the Old Mechanic’s Institute Gallery. I lived upstairs in the attic room and it was an amazing time, I was in my 20’s, there was a constant series of exhibitions and openings, artist talks, art classes, life drawing classes, a busy tea-room (herstory, pre café-culture). There were school student exhibitions, local artists and a constant flow of visitors in and out. As Mum became more interested in doing research trips on Mechanics Institutes, I covered the gallery for her. I loved sharing an interest in art with others. Mum taught me so much about building relationships, the importance of communications and a professional business approach. Some of the many things she has taught me and shared with me. Mum has been in this idea from the start. I’ve grown up in a home deeply passionate about our First Peoples, and about the environment. And I in turn have made a home with my son, deeply passionate about art, and the role of art to disturb, to comfort, to heal. Art in politics, art in societal change, art as a tool for celebration. When I got to Yuendumu last year, and met the Warlukurlangu Artists and the managers, Cecilia and Gloria, and the rest of the art centre team, the idea of coming back to Healesville and starting up a gallery cemented. My deep gratitude is to these people in Yuendumu, here today in spirit and in support. Coming home with this idea I received passionate support from friends, some supported the pop-up at the Senior Citizens Club, others sent constant messages of encouragement and moral support, from near and far. Even people I haven’t even met but know through facebook, including a lady, Dorothy, in the USA who ran a feminist bookshop for many years, sends constant messages of support! I thank Lana and Gary for helping with renovations on the last day of their holidays. I thank Em and Lola for helping with catering today and for Em’s deep calm that always got me through intense days at the botanic gardens. I thank Leila for searing intellectual debate and art lessons and I thank Ben for his wonderful canvas stretching. When I returned I wanted to meet Dr Lois Peeler AM at Worawa, knowing she had a connection to Yuendumu and Nyirripi too, she having been there, met the artists, and also having hosted a visit by Cecilia the manager here in Healesville. I thank Dr Lois, Lisa and the team at Worawa Aboriginal College for being an inspiring example of professionalism, hard work, passion, love and commitment. Today I am thrilled to have some extraordinary work by the Worawa students, including one by Tianna who is from Yuendumu. Heartfelt thanks go to my RBG sisters, lifelong friends, sacred rebels. There isn’t words enough to express my gratitude. You are here today some near some far, always by my side. Thanks to the friendly support of the West-end business owners. We will make the West-end rock. I’ve felt welcomed back home by your friendly faces. Last but not least I want to thank my family. I thank my dear son Alvaro for a wonderful careful painting job and our shared passion in art, nature and culture. His amazing help at the pop-up carrying endless things back and forth. I want to express my deep love gratitude and appreciation to Mum and her partner Rob. They have been into the idea from the start, immersed themselves in the three days of the weekend pop-up at the Senior Citizens, wrapping artworks, making tea, cooking meals, giving me a haven in transition. Rob who is new to the art scene is quickly becoming an aficionado! They have been up to the gallery every two days, helping with menial tasks, décor decisions and challenges, the fun and the hard slog, the creative decision-making processes. They are both amazing and inspirational and the biggest truth is I could not have done it without them. I hereby open hearth galleries with love, hope and gratitude. I hope you can join me in future exhibitions, indigenous, non-indigenous art, local and work from further afield, all speaking of the love and the stories of our shared earth Today I am also opening this brilliant exhibition of work from the Warlukurlangu Artists. More than a celebration of survival, more than a beautiful statement of colour and composition, this work gives us hope. Ancient iconography and jukurrpa (dreaming stories) told in contemporary styles ranging from expressionism, pictorial, naïve, blended with traditional, always a new way of using dots. Drawing us deeply into the ancient stories of this land and its ecological processes. I love the stories of plants like Desert fringe-rush Seed Dreaming, Lukurarra Jukurrpa, for example by artist, Serena Nakamarra Shannon. I love the stories of animals like the Brushtailed Possum Dreaming, Janganpa Jukurrpa and the amazing variety of interpretation within each of the Jukurrpas. I love the Karnta Jukurrpa or women’s dreaming stories like Valerie Napanangka Marshall’s iconic work. I hereby launch Warlukurlangu Artists and hope you enjoy it as much as I enjoyed bringing it to you! After a wonderful pop-up in the funky Senior Citizens Hall in Healesville, (see pics below) we decided to create an ongoing art-space in beautiful Healesville. We're calling it hearth galleries because it has the words 'heart', 'art' and 'earth' in the word, and a hearth is the place we, though the centuries, have sat down to share and tell stories, to learn and grow. It's been interesting to note that, as many people that do know the word, have not heard of it before! 'Hearth' must be an old word, perhaps even an old-fashioned one now! A loss of a word over one generation seems shocking; I grew into adulthood with the word, making fires and cleaning out fireplaces. I hope to bring a sense of hearth into this new art-space, I hope it will be a place of gathering on common ground, of conversation, of shared stories, the flickering light of learning and growth.

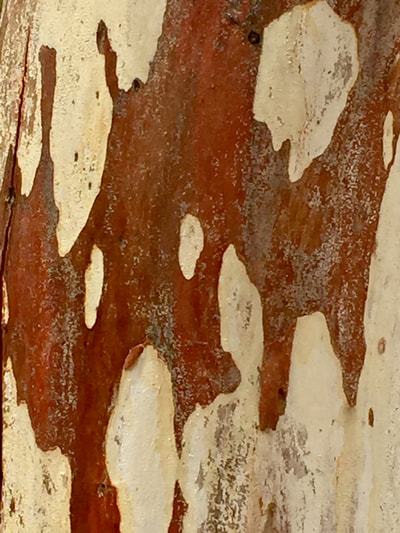

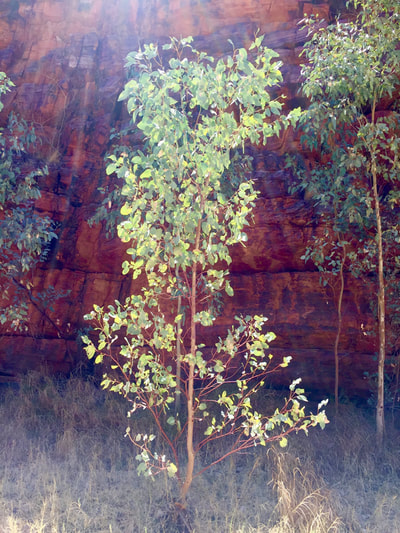

We'd love you to join us at hearth galleries for a sublime exhibition of work from Warlukurlangu Artists 2pm Saturday 12th May, 208 Maroondah Highway, Healesville. Connect to country with a drive and walk up Blacks Spur, named after the route taken by Aboriginal people, making their way to their ochre collection sites. Check out the giant Mountains Ash Eucalyptus regnans and collect some fresh spring water from St Ronan's Well. Hope to see you on 'the hearth'. Last September, after years of dreaming, then finally with compulsion, and accompanied by Tommy the dog, I headed north. A picture tells a story and so instead of a wordy blog I have posted a picturey one. Suffice to say, reddy orange and purply reds are the new pallet painted across my heart. Not only is the centre rich with colour, its vibrancy is borne from the people and culture of the centre, the desert people - My gratitude to the staff, artists and volunteers at Warlukurlangu Art Centre in Yuendumu is deep and wide. Thank you for providing the turn in the road. Thank you to the many others who encouraged and supported me before I left, along the way, and then held their arms open wide when I returned. This journey has changed my life and the new story begins. Here and Now. All photos copyright of Christine Joy, except Muffi waiting outside the shop in Yuendumu, photo credit Laura Roverso.

|

AuthorShare the adventure if you also love Aboriginal culture, art, nature, beauty and the stories that landscape tells us, when we listen and look with care. Archives

September 2021

Categories |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed